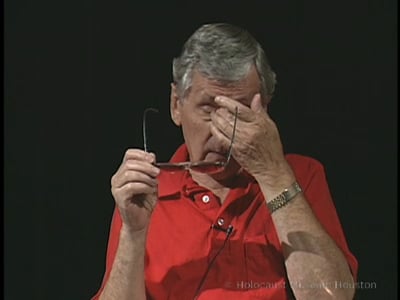

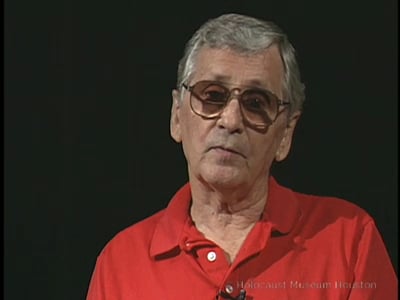

“Remembering the past kind of eats you up if you live with it. The best thing is to not really forget it, but not to live with it. I don’t go to sleep with it. I don’t wake up with it. I remember and it’s part of my life, but it’s what happened and you can’t do anything about it.”

The oldest of three children, Rubin Samelson grew up in Chorzów, Poland where his father owned a ladies’ dress shop. Rubin has fond memories of Jewish holidays spent with relatives and of time spent with friends, both Jewish and non-Jewish. The German invasion in September 1939 shattered Rubin’s peaceful existence. Shortly after Germany occupied Poland, Rubin’s mother and his younger sister Felicia were deported. Rubin never learned when or where they perished. Rubin’s father Henry was also sent to a camp, but he escaped. Captured by the Soviets, who accused him of being a German spy, he was exiled to Siberia.

Meanwhile, Rubin and his brother William, three years his junior, were herded into the Chorzów ghetto where they toiled in a glass factory. They worked in hot and grueling 12-hour shifts during which their only sustenance was watery ersatz coffee. When he was not at work, Rubin sometimes managed to sneak over the ghetto wall and smuggle back food to share with his brother.

In 1942, Rubin and William were sent to Częstochowa to work in a steel mill. As Russian troops approached, the slave laborers were loaded into windowless boxcars bound for Buchenwald. Many died en route. When they arrived at Buchenwald, Rubin and William were issued wooden shoes and striped uniforms. “We used to sleep 15 people to a bunk like sardines,” said Rubin. “As a matter of fact, if you got up in the middle of the night, you couldn’t get back in because your place was already taken.” He and William endured the horrific conditions in Buchenwald for about a year and were then sent to labor in a munitions factory in Colditz, Germany. One day the prisoners learned that they were to be evacuated. Rather than join the forced march, Rubin and William, along with about 20 other men, decided to hide. But their captors discovered them, forced them out into the yard and opened fire. At that moment, American troops arrived and the German guards scattered. Shocked at what they found, many of the American GIs broke down in tears. But the platoon leader had the presence of mind to take the ten surviving men—including Rubin and William—to a hospital in nearby Borna. Rubin later learned that these ten men were the only survivors of Colditz. The other 1,100 inmates had been murdered on the death march.

After recuperating, Rubin lived in Wiesbaden, Germany where he was reunited with his father. Rubin, William and Henry sailed for America in January 1948. Only four months after arriving in New York, Rubin enlisted with the U.S. Army. He was stationed in Germany, working with Army Intelligence as an interpreter, translator and interrogator. In 1958, Rubin moved to Houston. Rubin married Yaffa Benezra on February 24, 1960 and he worked as a hair stylist. Rubin and Yaffa had two sons, Harry and Aaron. Still active in retirement, Rubin volunteered at Holocaust Museum Houston and at Seven Acres Geriatric Center. He was a past commander of the Houston chapter of the Jewish War Veterans. A master glass blower, Rubin enjoyed photography and stained glass design.

Parents

Henry Samelson, survived

Balbina (Bella) Stebel Samelson, d. in Holocaust

Siblings

William, survived

Felicia, d. in Holocaust