The genocide began with massacres in the capital, Dhaka, on March 25, 1971, and soon spread to the rest of Bangladesh. The army had premade lists of targets, including members of the Bengali nationalists, intellectuals, and Hindus. The army believed that mass violence would terrorize what they saw as a racially inferior population into subservience, especially if Bengali elites were killed, but instead faced popular resistance that was put down with violence. Young men were targeted as potential sources of resistance and women and girls were raped as a way to destroy Bengali families. Despite a denunciation of the violence by the US consul general in Dhaka, Archer Blood, known as “the Blood Telegram,” the Nixon administration refused to intervene. A local guerilla movement gained support from India (a foe of Pakistan since Partition) and was able to force a Pakistani surrender in December of 1971. By this time, about three million people had been killed and millions more had become refugees in Bangladesh or India. When the army realized it was likely to lose, it targeted prominent individuals seen as a potential leadership for the new state of Bangladesh.

Justice for this genocide remains elusive. After a string of military coups in independent Bangladesh, the Awami League regained power and in 2010 initiated the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) to try genocide perpetrators. Pakistani perpetrators live abroad outside the reach of the court, so the tribunal focused on Bangladeshi collaborators, who did everything from propaganda efforts to identifying targets and participating in killing. This effort has been dogged by controversy, including allegations that has been used to target political rivals and concerns about due process and the use of the death penalty.

Sources:

Jahan, Rounaq. “Genocide in Bangladesh.” In Centuries of Genocide: Essays and Eyewitness Accounts, edited by Samuel Totten and William S. Parsons. 4th ed. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Jones, Adam. Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. 3rd ed. London: Routledge, 2017.

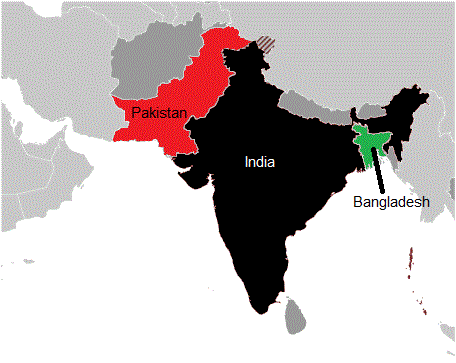

Source: edited from CIA World Factbook: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/in.html